Since man first made tools, utensils and weapons from wood, he has burnt, carved and scraped decoration into it.

Even in their simplest form, the rails and stiles of early joiner-made coffers usually exhibit chamfered edges (fig. 1), though more often the edges are decorated with intricate crisp mouldings (figs. 2 & 3).

Fig. 1. Plain oak panelled coffer. (Bonhams)

Fig. 1. Plain oak panelled coffer. (Bonhams)

Fig. 2. Oak linenfold coffer, sixteenth-century. (Bonhams)

Fig. 2. Oak linenfold coffer, sixteenth-century. (Bonhams)

Fig. 3. Moulded oak rails and stiles, late seventeenth-century. (Bonhams)

Fig. 3. Moulded oak rails and stiles, late seventeenth-century. (Bonhams)

The front carcase panels of coffers were, themselves, frequently decorated with carved linenfold, floral and geometric designs (figs. 2, 3 & 4).

Fig. 4. Oak linenfold coffer, mid sixteenth-century. (Bonhams)

Fig. 4. Oak linenfold coffer, mid sixteenth-century. (Bonhams)

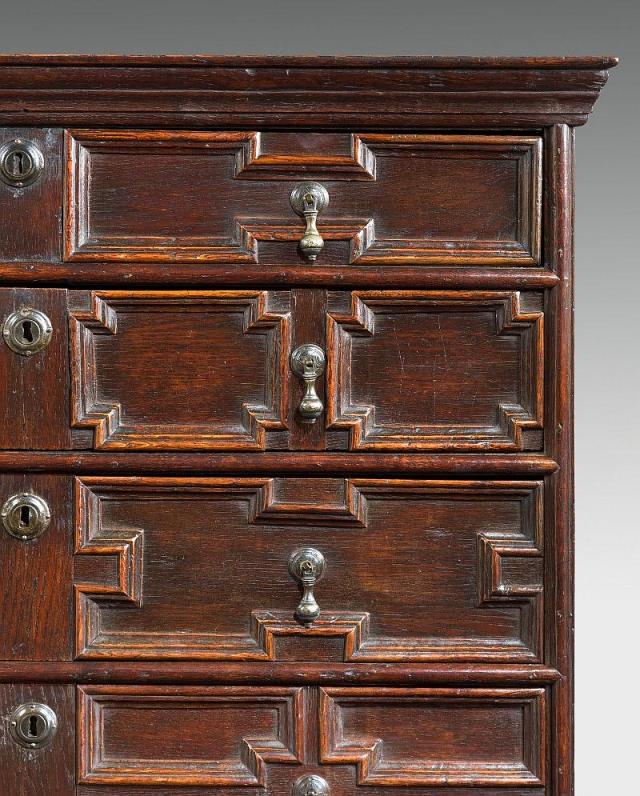

Square- and angular-moulded panels were also popular (fig. 5) which ultimately led to the practice during the third quarter of the seventeenth-century, of applying separately made mouldings to carcase panels in a vast array of geometric patterns (fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Square-moulded oak coffer, mid seventeenth-century. (Bonhams)

Fig. 5. Square-moulded oak coffer, mid seventeenth-century. (Bonhams)

Fig. 6. Geometrically moulded oak coffer, late seventeenth-century. (Bonhams)

Fig. 6. Geometrically moulded oak coffer, late seventeenth-century. (Bonhams)

Then one day a joiner (fed up with his wife’s constant complaining of having to pull everything out of her coffer to reach the things she wanted at the bottom) nailed the coffer lid down, removed the front panels and knocked some boxes together with grooves in their thick sides that ran on horizontal guide rails nailed to the inside of the carcase (fig. 7). That may be a falsehood.

Fig. 7. Charles II oak chest with side-hung drawers, circa 1680. (Horn Antiques)

Fig. 7. Charles II oak chest with side-hung drawers, circa 1680. (Horn Antiques)

At any rate, chests of drawers with solid frame and panel carcases (figs. 7, 8 & 9) endured until the early eighteenth century, but from around 1670, chests of drawers emerged with, at least, some veneered elements such as the carcase tops and drawer fronts (fig. 10).

Fig. 8. Charles II geometrically moulded yew chest, circa 1680. (Christie’s)

Fig. 8. Charles II geometrically moulded yew chest, circa 1680. (Christie’s)

Fig. 9. William and Mary oak moulded chest, circa 1690 (Thomas Coulborn)

Fig. 9. William and Mary oak moulded chest, circa 1690 (Thomas Coulborn)

Fig. 10. Transitional solid walnut frame-and-panel chest with walnut veneered top and drawers, circa 1685. (Wakelin & Linfield)

Fig. 10. Transitional solid walnut frame-and-panel chest with walnut veneered top and drawers, circa 1685. (Wakelin & Linfield)

These were interesting developmental times: Tastes and traditions die hard in the trades and the appearance, at least, of the old practice of framing the carcase sides carried over into all-veneered chests in the form of central vertically veneered ‘panels’ bound by ‘frames’ represented by veneer crossbanding (fig. 11). Note the earlier style of side-hung drawers commonly seen in frame-and-panel chests.

Fig. 11. James II walnut-veneered chest, circa 1685-88. (Streett Marburg)

Fig. 11. James II walnut-veneered chest, circa 1685-88. (Streett Marburg)

In the previous two examples, the veneered drawer fronts too, still retain decorative borders, though of feather- and cross-banding rather than applied mouldings. However, the heavy, long-grain, half-round mouldings of the token drawer dividers (figs. 7, 8 & 9) have now evolved into cross-grain D-moulding and have been applied to not only the drawer dividers, but also the inner front edges of the carcase.

For decades antique experts and furniture historians have cited crossbanding and cockbeading as being sacrificial trim, whose purpose was to protect vulnerable veneered carcase and drawer edges. As a furniture restorer and period furniture reproducer, this makes no sense whatsoever. Edge banding and cockbeading are a liability, not a defence: When substrate shrinkage occurs, applied mouldings and edge bandings are more likely to come away than larger veneers given their small footprints and glue areas. The mitred corners of cross-and feather banding are particularly vulnerable to knocks because of their short grain.

The veneer applied to the front edges of early veneered carcases merely served to hide the exposed edges of the (usually oak or pine) substrate from view. Had it been intended to protect the side veneer at the front corners of the carcase, it would have been much thicker – like the 3/16″ to 3/8″ thick carcase lipping on later veneered (and solid) chests.

The later, thick lipping was similarly applied to front carcase edges to conceal not just the secondary carcase wood from view, but also the dustboard joinery (previously hidden by the carcase-mounted D-moulding and double-bead moulding on earlier chests) due to the decorative moulding migrating again; evolving from drawer aperture D-moulding to (presumably) drawer periphery ovolo lipping and drawer periphery cockbeading respectively.

Thick lipping was simply easier and quicker to install than veneer, requiring only a few nails to secure it until the glue took hold.

There is another aspect to the use of cross- and feather-banding: While carcase sides were more often than not veneered with relatively plain veneers, the best, highly figured (often less expansive) veneers were reserved for the tops of carcases and drawer fronts, and the use of banding extended the bounds of the precious veneer.

Although one reads of some outstanding trees in old texts, most walnut veneers laid on furniture of the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century are not particularly wide. Carcases of chests of drawers of the period can be anywhere between 16″ and 23″ deep, though on average are 18″ to 21″ deep. The crossbanding on the same carcase sides is normally in the range of 2″ to 3″ wide, leaving the major veneer anywhere from 12″ to 17″ wide. As the great majority of carcase top and side veneers are bookmatched (or quartered), the actual width of veneer required may be as little as 6″. The vertical sections of veneer on drawer fronts (typically numbering four, six or eight) may be as little as 4″ wide.

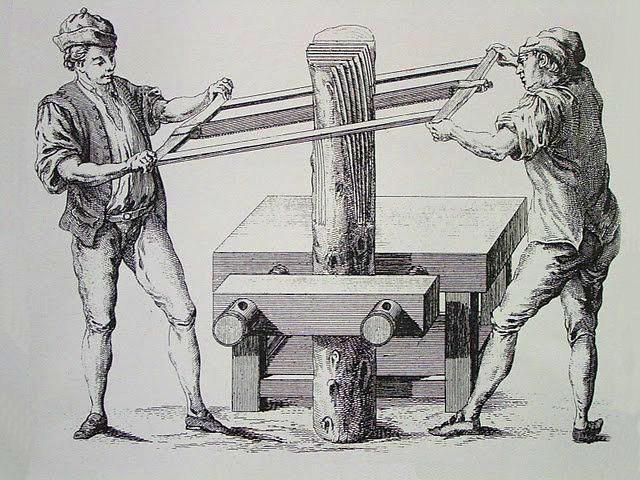

One might assume that book matching and quartering were carried out purely for aesthetic purposes, but there may have been more practical reasoning at play. Roubo illustrates a pair of sawyers sawing veneers from a small diameter log (fig. 12).

Fig. 12. André Roubo’s veneer cutters, circa 1769-82.

Fig. 12. André Roubo’s veneer cutters, circa 1769-82.

The small size of the log may not be truly indicative, however, Roubo is renowned for the accuracy of his illustrations and the sawyer’s vice certainly wouldn’t hold a very large log.

Some exceptional late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century cabinets sport highly decorative wide veneers, but in the main, bookmatched panels were the norm. Perhaps the cutting of wide veneers of consistent thickness couldn’t always be guaranteed with the prevailing saw blade technology and more veneer (and thus, money) could be dependably extracted from smaller logs. I just don’t know.

Banding is unarguably decorative, but more importantly, it allowed skilled joiners and cabinetmakers to stretch valuable figured veneers to cover the broad expanses of carcase panels and banks of drawers.

The lion’s share of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century cross- and feather-banding surprisingly, remains intact and in reasonable condition. In the course of my work, I have replaced missing bits of crossbanding on drawer fronts (and replaced many others’ poor repairs), but in the majority of cases, the damage was simply due to dried-out glue or long term wood movement and likely would not have occurred during the makers’ lifetimes (or those of their immediate predecessors or successors), so why would a joiner or cabinetmaker concoct a remedy for a nonexistent or unforeseeable event?

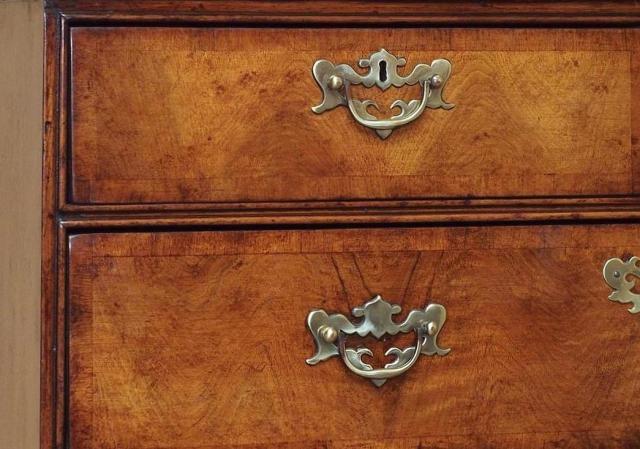

Bead mouldings first appeared as decorative embellishments on moulded chests and logic would dictate their evolution to be: carcase-mounted D-moulding (fig. 13); carcase-mounted double-bead moulding (fig. 14); drawer aperture cockbeading (fig. 15); drawer periphery cockbeading (fig. 16). However I haven’t seen evidence for drawer aperture cockbeading preceding drawer periphery cockbeading (I would welcome evidence that would overturn my thinking).

Fig. 13. Carcase-mounted crossgrain walnut D-moulding, circa 1690.

Fig. 13. Carcase-mounted crossgrain walnut D-moulding, circa 1690.

Fig. 14. Carcase-mounted crossgrain double-bead walnut moulding, circa 1720.

Fig. 14. Carcase-mounted crossgrain double-bead walnut moulding, circa 1720.

Fig. 15. Drawer aperture long-grain walnut cockbeading, circa 1725. (Royal Antiques)

Fig. 15. Drawer aperture long-grain walnut cockbeading, circa 1725. (Royal Antiques)

Fig. 16. Drawer periphery long-grain walnut cockbeading, circa 1725. (Reindeer Antiques)

Fig. 16. Drawer periphery long-grain walnut cockbeading, circa 1725. (Reindeer Antiques)

Bits of mouldings have been popping off Carolean chests for centuries (undoubtedly during their makers’ lifetimes too), so it’s implausible that later cabinetmakers would stick long-grain cockbeading onto the ends of drawer fronts if not for overriding reasons of aesthetics or fashion. However, one advantage of cockbeading was that it partially covered the exposed end grain of drawer fronts – which, by limiting the absorption and release of moisture through the end grain accomplished a degree of self preservation.

Based on my experiences as a restorer of almost four decades, the edges of plain- and even japanned drawer fronts (figs. 17 & 18) seem to have survived relatively unscathed, whereas the fragility of cockbeading often necessitates its repair or complete replacement.

Fig. 17. James II oak chest (later feet), circa 1685. (James Graham-Stewart)

Fig. 17. James II oak chest (later feet), circa 1685. (James Graham-Stewart)

Fig. 18. James II japanned drawers, circa 1685-88.

Fig. 18. James II japanned drawers, circa 1685-88.

Because of the manner in which cockbeading protrudes from the face of a drawer, it is itself, vulnerable: Even vigorous buffing with a soft cloth has been known to pop a piece of cockbeading off. Shrinkage and dried-out glue can also lead to cockbeading just popping off of its own accord if not originally nailed-on as well.

Another form of drawer edge decoration, ovolo-moulded lipping, (figs. 19 & 20) enjoyed brief popularity between, roughly, the years 1730 and 1760.

Fig. 19. Solid mahogany ovolo-lipped drawer, circa 1750.

Fig. 19. Solid mahogany ovolo-lipped drawer, circa 1750.

Fig. 20. Solid mahogany ovolo-lipped drawers, circa 1760.

Fig. 20. Solid mahogany ovolo-lipped drawers, circa 1760.

Moulded, lipped drawers – whether long-grained or applied crossgrained (fig. 21) varieties – are particularly susceptible to damage.

Fig. 21. Damaged (and badly repaired) crossgrain ovolo-lipped drawers, circa 1730. (Robert Walsh)

Fig. 21. Damaged (and badly repaired) crossgrain ovolo-lipped drawers, circa 1730. (Robert Walsh)

Attaching cockbeading was fiddly work, but lipping drawer edges was intensely laborious, affecting more than just the decorative element: The applied cross- and long-grained lipping on veneered drawer fronts could, in theory, be attached after cutting the lapped dovetails, but the lip on solid drawer fronts hindered the cutting of lapped dovetails. What’s more, drawers that were lipped on all four sides made it much more difficult to plane the bottom of the drawers’ runners during final fitting of the drawers to their openings. For this reason, some lipped drawers – while ovolo-moulded along all four edges – were only lipped along the side and top edges. Lipped edges are fragile and difficult to repair, so if not in the name of fashion, why were drawer edges routinely lipped for a period of thirty years?

It is plainly evident from written records and physical evidence that seventeenth- and eighteenth-century craftsmen worked at a brisk pace that any committed twenty-first-century self-employed worker would be familiar with – forming dovetails is one example. It’s unrealistic to think these joiners and cabinetmakers would spend countless hours adding protective elements to their cabinets, chests and tables when unpredictable events were beyond their control – and responsibility. Their objective was to produce neat, sound and fashionable goods.

Driven by shifting fashions, carcase and drawer decoration was simply that.

Jack Plane

Thank you again for the education, you constantly amaze with your in depth knowledge, experience, and willingness to educate

LikeLike

It keeps me off the street corners.

JP

LikeLike

Interesting how on the front of the chest in Figure 4, the reeding on the bottom of the frame rail above the panels just tapers out of existence above the stiles. The same sort of thing happens on the frame rails above and below the panels on the front of the coffer in Figure 5.

LikeLike

As those particular mouldings were made with scratch stocks rather than planes, they simply tapered them off when they reached a stile. It was widespread practice.

JP

LikeLike

Interesting how little the form has changed. Do we know the earliest date for a chest of drawers?

Thanks Don

LikeLike

There wasn’t much of anything prior to the restoration of Charles II. It’s difficult to be precise, but I would say the first English-made chest of drawers probably appeared around 1660-5.

JP

LikeLike

Another excellent post, Mr. Plane. Best wishes in the New Year.

LikeLike

And to you too.

JP

LikeLike

Very interesting article and a brief history of Drawers as well.

LikeLike

Thanks for the excellent post Mr. Plane. Quite an enjoyable read.

LikeLike

Pingback: Picture This XC | Pegs and 'Tails

Hi Jack,

old craftsmen used to varnish the end grain of the piece with the pins in the drawer sides, for reducing the effects of seasonal movements, or in the long time isn’t of such value?

Thanks.

LikeLike

I can’t speak for later nineteenth- and twentieth-century casework, but I have never encountered a single eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century drawer front whose end grain was originally sealed.

I have however, seen plenty of drawer fronts whose end grain was subsequently varnished as a consequence of sloppy restoration (as opposed to any cognizant effort to reduce the uptake of moisture).

JP

LikeLike

Thanks. Yes I was thinking that it is better to reduce the amount of exposed end grain or if the varnish can play a good role in this perspective. I have a 1939 case furniture where the drawers fronts are now out of square, and there arent’ cockbeading or varnish, simple half lap dovetails, so I don’t know if they would go out of square anyway.

Valerio.

LikeLike

I think it’s more likely your out-of-square drawer fronts are due to poorly selected timber.

JP

LikeLike

Pingback: Picture This CXXIV | Pegs and 'Tails