There has been a recent surge (if two emails in the same week qualifies as a surge) of enquiries regarding the appropriateness of ‘finishing’ (in the modern tongue, applying some sort of varnish or lacquer) the interiors of drawers and casework in general.

I got the distinct impression both writers had recently discovered that brushing on spirit varnish doesn’t involve the sorcery they were previously led to believe, and were now enthusiastically seeking other surfaces to apply their new-found talent to.

On approaching the completion of a project, some individuals just can’t resist garnishing their creation, but finishing interiors is an evil canard promulgated by a handful of equally disturbed nineteenth- and twentieth-century authors.

My usual response to these enquiries is, “Aside from the majority of bureau and secretaire writing compartments, polishing or varnishing interior surfaces is plain wrong, don’t do it!”

Contextually, I am of course correct! However, that’s not to say that early craftsmen and cabinetmakers didn’t, on occasion, apply something to various secondary surfaces.

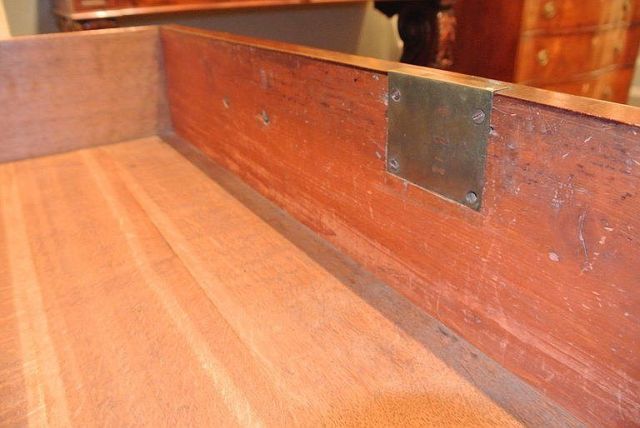

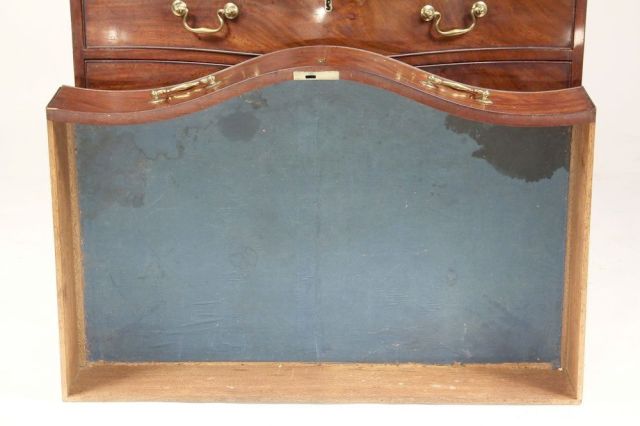

Since the advent of furniture, certain non-show surfaces have received thin coloured washes (with the minimum of fixative: The surfaces therefore aren’t technically sealed) for either decorative or practical purposes (figures 1, 2 & 3).

Fig. 1. Pigment-washed backboards, circa 1685.

Fig. 1. Pigment-washed backboards, circa 1685.

Fig. 2. Minium- and/or pigment-washed backboards, circa 1790.

Fig. 2. Minium- and/or pigment-washed backboards, circa 1790.

Fig. 3. Unusual washed interior of mahogany chest-on-chest carcase, circa 1760.

Fig. 3. Unusual washed interior of mahogany chest-on-chest carcase, circa 1760.

Mahogany-red pigment washes were often employed to lift the appearance of cheap pine components in mahogany furniture (figures 4, 5 & 6).

Fig. 4. Oak-lined mahogany drawer with red-washed pine back, circa 1770.

Fig. 4. Oak-lined mahogany drawer with red-washed pine back, circa 1770.

Fig. 5. Red-wash applied to reverse of pine drawer front of a mahogany-veneered chest – the drawer, otherwise oak-lined, circa 1780.

Fig. 5. Red-wash applied to reverse of pine drawer front of a mahogany-veneered chest – the drawer, otherwise oak-lined, circa 1780.

Fig. 6. Another oak-lined ‘mahogany’ drawer with thinly washed pine front, circa 1780.

Fig. 6. Another oak-lined ‘mahogany’ drawer with thinly washed pine front, circa 1780.

The pine secondary wood interiors of mahogany-veneered casework were also routinely given a red wash (figures 7 & 8).

Fig. 7. Mahogany-veneered bookcase and cabinet with red-washed pine interiors, circa 1780.

Fig. 7. Mahogany-veneered bookcase and cabinet with red-washed pine interiors, circa 1780.

Fig. 8. Mahogany-veneered bookcase with red-washed pine interior, circa 1780. Note the panel shrinkage in the right hand door exposing the raw pine.

Fig. 8. Mahogany-veneered bookcase with red-washed pine interior, circa 1780. Note the panel shrinkage in the right hand door exposing the raw pine.

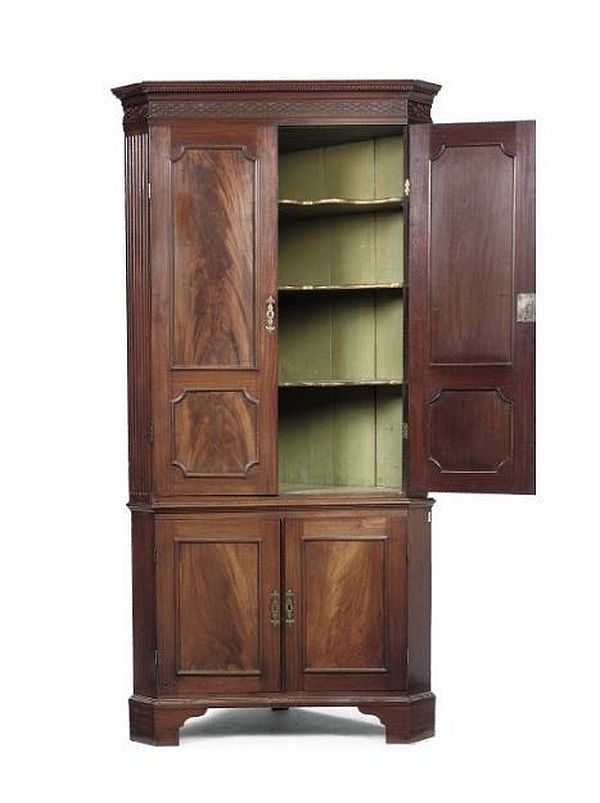

The interiors of various cabinets and in particular, corner cabinets were frequently painted in off-whites and shades of duck egg blues and greens (figures 9, 10, 11 & 12).

Fig. 9. Walnut mural corner cabinet with cream painted interior, circa 1740.

Fig. 9. Walnut mural corner cabinet with cream painted interior, circa 1740.

Fig. 10. Corner cabinet with dark green painted interior, circa 1760.

Fig. 10. Corner cabinet with dark green painted interior, circa 1760.

Fig. 11. Mahogany corner cabinet with cream painted interior, circa 1775.

Fig. 11. Mahogany corner cabinet with cream painted interior, circa 1775.

Fig. 12. Mahogany corner cabinet with duck egg green painted interior, circa 1780.

Fig. 12. Mahogany corner cabinet with duck egg green painted interior, circa 1780.

Drawer bottoms also came in for a bit of attention in the form of paper lining, which one might imagine would be for the practical purpose of sealing bottoms with split boards. However, one often sees paper-lined drawers whose bottoms have split subsequent to being lined (figure 13).

Fig. 13. Split paper-lined drawer, circa 1770.

Fig. 13. Split paper-lined drawer, circa 1770.

Early lining papers were small, block-printed sheets that were laid haphazardly on the bottoms of drawers (figures 14, 15, 16 & 17).

Fig. 14. Block-printed lining paper, early seventeenth-century.

Fig. 14. Block-printed lining paper, early seventeenth-century.

Fig. 15. Block-printed lining paper, late seventeenth-century.

Fig. 15. Block-printed lining paper, late seventeenth-century.

Fig. 16. Block-printed lining paper fragment, circa 1715.

Fig. 16. Block-printed lining paper fragment, circa 1715.

Fig. 17. Walnut drawer with pieced paper lining, circa 1720.

Fig. 17. Walnut drawer with pieced paper lining, circa 1720.

Sugar paper (the pale blue paper traditionally used to wrap loaves of sugar) was employed for lining drawers in the latter decades of the eighteenth-century (figures 18, 19 & 20).

Fig. 18. Sugar paper lining, circa 1775.

Fig. 18. Sugar paper lining, circa 1775.

Fig. 19. Sugar paper lining, circa 1790.

Fig. 19. Sugar paper lining, circa 1790.

Fig. 20. Dwarf linen press drawers lined with sugar paper, circa 1780.

Fig. 20. Dwarf linen press drawers lined with sugar paper, circa 1780.

Linen drawers were also occasionally lined with marbled paper.

Jack Plane

Sheraton pink we used to call that red powdery coating.

It’s been a while since I’ve done this and can’t remember the exact solution but some pieces of furniture I would wash the drawer interiors with a mix of gum turps and water. Horror!?

LikeLike

Thank you, always a learning experience to read your post.

LikeLike

Great read. OK I respect your opinion but I am still going to put a finish on the inside of my drawers. If no other reason I like it.

LikeLike

I hear you: There’s no substitute for that silky feeling next to the buttocks.

JP

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the information.

LikeLike

Is the red wash anything more that iron oxide red and water?

LikeLike

The constituents of early washes were either genuine minium pigment (or a cheaper substitute of yellow ochre mixed with a red such as burnt sienna) and size for the fixative.

Later washes often comprised solely a red pigment (for the colour) and size. Venetian red appeared mid eighteenth-century.

JP

LikeLike

A very interesting post, thank you Jack. The red wash you refer to I always knew as “Venetian Red” and made it up with that pigment and glue size. On lining papers – I have seen these in a piece of late 16 c furniture and while we are in the subject – in the 17 c Rucker’s Harpsichords were often decorated with printed lining papers simulating veneers and inlay.

LikeLike

Indeed some of the Flemish harpsichords were beautifully lined with ornately printed paper as well as painted landscapes and scenes.

JP

LikeLike

Very Interesting. In 18th and 19th century boxes of a type made by trunkmakers and covered in leather we have also come across lining paper made from block print on top of either old newspaper or book pages.

LikeLike

For some of us that do not have access to museums and high end antique stores your wealth of knowledge is invaluable. So two questions:

Were the inside of interior drawers in the gallery finished, I’m guessing not.

Recently I have read suggestions to coat drawer interiors with a beeswax/solvent (usually turps) mixture. Have you seen or suspected such a polish?

Thank you, PGOster

LikeLike

The drawer fronts, alone, of enclosed case furniture (escritoires, bureaux, dressing chests and secretaires etc.) were often dry-finished; that is to say, exceedingly thinned down wax polish (see below). The linings were always left raw.

JP

LikeLike

I’ll volunteer ~as tribute~ to ask the stupid question:

_Why_ is it wrong to finish the inside with something?

Does it not help equalise drying between inside and outside if the relative humidity of the environment changes or is that a bit of an urban legend like searing a steak to seal in the juices?

LikeLike

Polishing internal surfaces does nothing for equalising moisture content of wood and I have never encountered an internal wooden surface that required equalising. It’s wholly unnecessary.

Most film finishes, when subjected to friction (as when a loaded drawer is pushed/pulled in and out of a chest), melt and become a gummy mess which would be inclined to hinder a drawer’s operation.

At any rate, the pros and cons of sealing interior surfaces are moot: It simply wasn’t practiced in the seventeenth-, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-centuries (I can’t speak with any authority for later decades when virtually everything went egg shaped at the hands of the Victorians).

JP

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jack, appreciate the reply. Especially when it means I can skip work in the future with a clear conscience :D

LikeLike

I have a late 18th century slant desk with drawers that are similar to figure 3 with the “unusual” washed interior. I was always concerned that this was a failed attempt to age the drawers. Is this something that was original to the drawers or does this sort of thing happen later in life? Do you have any idea of the process that goes into this?

Thanks.

LikeLike

Without inspecting the desk, my guess is the drawers were probably washed over retrospectively. Drawers were often lined with paper retrospectively too.

JP

LikeLike

Excellent and valuable insight into a topic few books cover. I have seen many of these examples over the past 50 years of conserving furniture. I would mention one you did not list, perhaps as you are mostly looking at English pieces: the robin’s egg blue paint used by the Seymours in their fantastic Federal furniture.

Your blog is great.

LikeLike

Thank you for this post! I have a desk that has a red wash applied all over the inside of the drawers and underside (similar to figure 4.) There is some wood shrinkage revealing the raw wood on my drawer bottoms and the underside of the desk where the top attaches to the frame. (similar to the door in figure 8.) I am glad to know that I am not crazy to think that this desk could possibly be an antique! I have been told that the wash on the interior is a sign that it was made by someone trying to fake age. I would love to send pictures to get a real experts opinion if that is possible. Thanks again for your posts. They are fascinating.

LikeLike

I’m a fake expert.

JP

LikeLiked by 2 people

The secretary and bookcase with the adjustable shelves, how typical were shelves like that? I had the impression it was more of a modern development to have adjustable shelves and that historic examples typically had fixed sizes based on common book sizes.

LikeLike

The earliest adjustable shelves I have seen were circa 1685.

JP

LikeLike